My School Years

In my early school

years the burgh

of Earlsferry didn't have a school for the elementary grades so all the Earlsferry children went to

the school that did at the neighboring burgh of Elie. My school years were a wonderful

time in my life. That is, except for the first week. On the first day my

parents had dressed me up in a complete new outfit. New black leather boots,

heavy knee length woolen stockings, knee length cotton under garment "combies",

woolen trousers, new flannel shirt, a

tie that strangled me and a heavy woolen jacket. As each stiff new garment went on I

became greatly alarmed as my temperature and my temper rose. By the time I was

outfitted I was terrified. All my life I'd roamed free. Free as

the wind. All summer long I ran barefoot. I'd no need or use for shoes. At

low tide I could run over the slippery tangles, the seaweeds and the barnacle

covered rocks. And I don't mean slowly. I was so sure footed in my bare feet

that in this element I was a gazelle and I never felt cold. Even when I got

soaking wet from the sea. And now this, dressed up to kill like a

mannequin in a tailor's shop

window. No, I wasn't going to school. If this is what it took, I

wanted none of it. School must be an awful and terrible place

if this is what it took to go there. Nobody was going to do

this to me. I started to remove the stiff new clothes that I

was wearing. Then my parents laid down the law. "You're going to school and you're going respectable." It became a

tug of war. I

remember the second day was almost a repeat of the first. Slowly, I gave in. I

give full credit for that to Miss Mowat. My liking school didn't happen all at

once but

within three months I was eagerly running to get to her classroom. As a young boy and right

in to my teen years I never walked. Everywhere I went, I ran. Soon, each

day, I was running two, two mile, round trips between home and school in record

time.

I

remember Miss Mowat's amazement when she discovered that I knew

how to count and knew intervals of time. This was all due to

the

Elie Lighthouse.

Each

night I went to sleep counting the flashes of the lighthouse as

the rotating beam of light reflected on to the ceiling of my

bedroom. I

was sorry when my two years with Miss Mowat ended as she'd won

me over to the point that I'd become teacher's pet, the

chosen one who

got to clean her white chalk blackboard.

After

Miss Mowat came Annie Don. She was a different proposition.

She ruled with an iron rod. None of this lovey-dovey

dangling the

carrot stuff for her. She believed in the hammer. No boy or

girl was going to get away from her without everything she

taught being thoroughly pounded in. By the fifth grade she had

us singing the multiplication tables up to twelve times

twelve--and liking it.

In

addition to the scholastic subjects, Mr. Harrison, who was the

headmaster, (and succeeding him Mr. Beveridge) taught and gave

us a love for gardening. In the thirties the Elie School had

quite a large piece of garden ground where a stone wall separated

the school from the golf course. All children

participated in the making and the upkeep of the garden. A

wooden shed housed all of our garden tools. On the walls we

espaliered fruit trees and each of the school year classes had

its rectangular vegetable garden plot. We drew a diagram

of the plot on paper and voted on what we would

grow. We calculated how many rows of this and that we'd

grow and how many seeds we'd need. As well as being

great fun it was a valuable learning experience. At the end of

the school year we harvested, divided up and took home the

fruits of our labors.

The end

of each school year was marked by Prize Giving Day. Right behind the school, on

the golf course, a table was set up which got loaded with the many beautiful

books that were to be presented for this or that scholastic achievement. Chairs were set

out on the grass to seat all from the village who came for the event. The last

and final prize that I won was the Moncrieff Prize. It was for the boy most

likely to --- . Helen Greig, who'd been my counterpart and main competitor all

these years at Elie School, won the prize as the girl most likely to ----.

And so it

was on to The Waid Academy

Each day

going to the Waid Academy was a great adventure as to get there

we traveled from Elie to Anstruther on the LNER, East of Fife

coastal railway. A great belch of smoke signaled the arrival of the

steam engine train as it emerged from the tunnel to stop at the

Elie railway platform where it puffed and panted when not in

motion. The train had a driver and a fireman,

whose job it was to shovel coal into the boiler's firebox.

These pair understood boys. Each day from a different village

along the way two boys were invited to ride the footplate and be

firemen for the day. Sometimes we got to start the engine in

motion as we got to pull the lever that caused steam to flow

from the boiler to the driving cylinder of the engine. Often our clean shirts were coal smudged

by the time the train, which made stops at St. Monans and

Pittenweem, arrived at Anstruther.

Some times we arrived late at the station to find that the train

was in the process of leaving without us. When this happened

there was just time enough to sprint back up to the coastal road

to hopefully catch the Alexander bus that arrived at

Anstruther at about the same time as the train. The conductress

on this scheduled bus was usually a rosy cheek and red haired,

born and bred, "Siminins" young lady. She was a no nonsense

"clippie" who wasn't about to tolerate the youthful exuberance

of boys and/or the copying of homework on her bus. No sir, that

bus was her domain and in no uncertain terms she let us know it.

She knew what made boys tick and reigned with a smile and a

twinkle in her eyes. When the bus arrived at Anstruther, in a

loud, enthusiastic voice she'd call out, "Enster, Enster. Aw them that's here

for there get aff for this is it."

At Waid,

Tom Croal was gym teacher. Miss Nisbet (Nizzy), who

bestowed on me the classroom name of Pierrot, (P err O) taught

beginning and medium level French. Next room to her was Miss

(granny) Sangster, who preferred to be

thought of as an 'unclaimed blessing', taught

higher French and German. Mr. (Bully) Allen taught Math in general. Next came

Jackie Whyte, who taught higher Math. Jack (Chuck)

Liston and George Napier both taught Physics, Science and

Chemistry. These were my favorite classes, especially on

the days that we pulled apart Magdeburg hemispheres

to demonstrate the pressure of the atmosphere on a vessel when the contained air was evacuated or fired up

Bunsen burners to make and calibrate glass tube thermometers and thirty

two inch

long, Admiral Fitzroy style, mercury filled and open to the

atmosphere, glass J

tube barometers. Mr.

(Tempus Fugit) Tammy Young, at the top of the stairway, taught Latin. Mr. Gourdie taught Geography. Mr.

Sutherland taught Art, Miss (Annie) Duncan taught History.

Alistair Crichton taught English as also did Mr. (Bill)

Ferrier. Mr. (Danny) Blair taught us the meaning of

and to sing Gaudeamus

igitur and music in general and was responsible for

the first thing in the morning prayer session. Danny Blair

was Master of his Art when it came to multitasking

and while piano/Handel

was his forte, all at once and without us realizing it, in one

fell swoop as well as poetry he would be teaching us singing, voice control, diction, elocution, Shakespeare,

you name it! Mr. (Cocky)

Robin taught mechanical drawing and woodworking.

Mr. William Wishart Thompson (aka Sharky), was the Rector

(principal) of the school. Our use of first names and nicknames

were truly all words of endearment.

Bill

Ferrier was definitely a disciple of Omar with his tent and his

flask of wine, his loaf of bread and his book of verse.

His literary bible was Palgrave's Golden Treasury.

Bill Ferrier was every bit an artist as was Vermeer only instead

of using paint brush and canvas to preserve his creativity and

artistry Bill Ferrier used words. His pupils were his

canvas. A picture is worth a thousand words but not when it

applies to Bill Ferrier's artistry. The four years that I had

the privilege to be tutored by him are just as alive in me today

at 92 as when I was 15. The visuality and pathos he put

into Burns' observation of, the wee cowrin timrous beastie;

the gleam in the eyes of the parents in, the Cotters

Saturday night; the solitude of Wordsworth's, I wandered

lonely as a cloud; the life long search for each other in Acadia

of Evangeline

and Gabriel; the wailing of the wind across

the mere in The Death of King Arthur; Portia's, The

quality of mercy is not strain'd---; the shivering cold

that we actually felt as he intoned,

"St.

Agnes' Eve, Ah, bitter chill it was!

The owl

for all its feathers was a-cold;

The hare

limped trembling through the frozen grass,

And

silent was the flock in woolly fold :

Numb were

the Beadsman's fingers, while he told

His

rosary, and while his frosted breath,

Like

pious incense from a censor old

Seemed

taking flight for heaven, without a death,

Past the

sweet Virgin's picture, while his prayer he saith".

I defy

any artist's painting to come anywhere close to the mystique of

the invisible portraits that Bill Ferrier painted with his use

of poetic words. Mr Ferrier involved and enlightened us as he painted his word

portraits of many hundreds of such passages. Like me I'm sure that all of

his pupils who are now in their 80's and 90's still remember him vividly

and see him as he adjusted and looked over the top of his

glasses as he exposed us to yet another of his pearls of wisdom.

Bill Ferrier constantly

shed his wisdom as he projected his brain to live on and grow in the

brains of every one of us who were his pupils. The invisible transfer of brain

cells from one person to another creates an everlasting chain which

has caused me for one to believe that no one ever dies. Like Bill Ferrier there

are numerous persons in our lives who are all living on and growing

inside of our brains to make us the composite hosts that with the passage of

time we all have become. From day one, without the input of our mothers and

fathers, our teachers and others too numerous to count, we could not be and

would not be who we are today. With the passage of time our body parts wear out and finally cease to

function but the, who we are,

keeps fanning out and growing in the brains of the thousands of individual others whose paths have

crossed ours,

endlessly----forever----ad

infinitum.

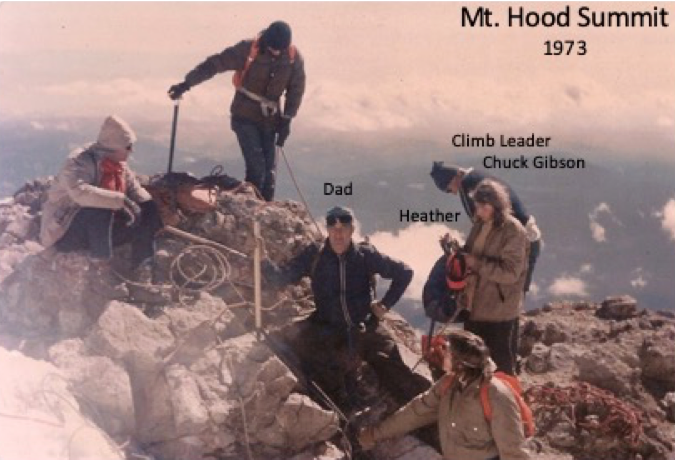

Today ( 5-22-09) by

coincidence, I was standing in a check-out line. I looked at

the man standing in line next to me and said to him, "You're

Chuck Gibson. (he was). In 1973, 36 years ago, you were the leader of a group

of five aspiring climbers that included me, my 17 year old son Mark and my

15 year old daughter Heather that you successfully trained and led to

the summit of Mt. Hood. You made a big impact on our

lives."

Mt. Hood at 11,239 feet

high is the highest mountain in the State of Oregon. I don't

know if Chuck Gibson is "still around" but the Chuck Gibson

component that

lives on in us has been climbing up mountains and scrambling up hills

ever since.)

When

we made this 1973 Mt. Hood climb we arrived on the mountain the night

before where we slept for a few hours in sleeping bags in the Wy'east

mountain climber's hut. Outfitted with ice axes, heavy

climbing boots, crampons, carabineers, ropes, warm clothing,

dark goggles, water, food, compass, survival gear etc. we set off by the light of the

moon at 2 o'clock in the morning. We climbed by way of

Illumination Rock and the Hog's

Back Ridge on the south side of the mountain, traversed the

glacier and the deep

crevasse that is just above this narrow ridge, held our noses to

get past the smoking sulphur fumaroles, roped up when conditions

were such that we should do so and by 10 we

were standing on the top of the mountain where we recorded our names and the date

in a ledger

that's kept there for this purpose in the Mazama's waterproof iron lock box.

11,239 feet. On the summit of Mt. Hood 1973

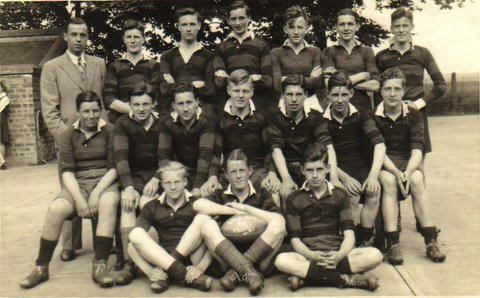

Mr. Liston our science teacher was also our rugby coach. He

knew just how to get the most and the best out of us. I

never made the first fifteen but several times I was good enough

to captain the second team.

1941 Waid Rugby

Team First XV

The captain is Bill

Cunningham.

Lower right is Sydney

Ferguson and lower left is Sydney Gowans, both from St. Monans.

Second from the right in

the back row is Elie's Bert Stewart.

A few of the others whose

names I think

I remember-----

Next to Chuck Liston,

David

Robertson. Then Butch and Gus Sleeman. (Yankee brothers)

Middle row, far left, XXX

Stevenson. Middle row far right, George Wilson from Colinsburgh

and next to him, Andrew Peddie from the Coal Farm, St. Monans.

(His younger sister Mary Peddie and I were in the same class

year)

(After

75 years don't hold me to being right on any of these

who I have named.)

I really loved all of my years at the Waid. They were great. I

can't say enough about these great teachers. They brought to

life the poets of the past and the authors of the classics.

They gave meaning to the teachings, the values and the wisdom of

our predecessors. They instilled relevance to all of their

subject specialties. To this day I remember most of what I

was taught. The one thing that I most got from the Waid is that

black is black and white is white. Shades of gray are the domain of thinking,

speculating and believing and should be kept in perspective. When all's said and done you

either know or you do not know. You can speculate, believe and

think all you want to but a skyscraper or the process of thought must be built from bedrock on up upon a solid series of

steps of factual information. The organization of

knowledge BIF (Basis In Fact).

Many

years later on behalf of Tektronix I was reminded of BIF when I was invited to

visit the Boeing Airplane Plant at Everett Washington. At that time the

747 was just a number. There on the runway sat the, as yet not

flown, prototype. My host graciously and proudly gave me a

personal tour of it's inner workings. It dwarfed every other airplane I'd ever seen. I

was awestruck. For its day it was monstrous. How could such a

many tons of weight behemoth get off the ground? I asked my host, "Do you really

think it will fly? Do you really believe it will ever get off the

ground?" He looked me straight in the eye and with a somewhat

jaundiced look he gave me an emphatic, NO. I don't

think it

will fly. However, when the day

comes that we align it up with the runway for its first

take-off, we advance the throttles and the engines spool

up to full power, we release the brakes and it

accelerates along the runway, we at Boeing know precisely how many feet it will

travel before it lifts off. We know the lift coefficient

of the airfoil so we know how much lift is generated from each square foot of wing

and surface that generates lift.

We know its weight. We know the thrust of the engines. We

know what the drag is. Thinking,

speculating, hoping and believing are bottom rungs on our

ladder. At Boeing we get to the top rung. We know

exactly why we do what we do.

In all

seriousness, he asked, "Would you want to fly on anyone's

airplane whose engineers merely thought or believed it would fly?" He made his

point. BIF - one of the many things that Waid Academy

taught me.

As events turned out the Boeing 747

became the airplane that would change the entire world.

|